If we manage to keep Elias in Sona’s belly until her due date, I only have 22 days left as the momma of only one boy. And, judging by how things are progressing, I don’t think we’ll make it the full 22 days.

We are ready for Elias to be here. The house is in order. The baby clothes are washed (and soon to be put away). All of Finn’s baby gear has been pulled out of storage, reassembled, and cleaned.

I am prepared for Elias. But, if I’m being honest, I don’t feel at all prepared to share my heart with another little boy.

Please don’t write to me, telling me that your heart grows. That you find the love. That the minute Elias is born, all will be right in our family-of-four world. I know these things to be true. I believe these things will happen.

Yet, this isn’t a post about logic or reason. This is a post about how I’ve found myself in tears numerous times in the past couple of weeks, trying to imagine what life will be like when I can no longer give Finn 100% of my love and attention. I’m crying now, just thinking about it, again.

Yesterday, Sona found out she is 3cm dilated and 70% effaced. The news set us into a frenzy of anxiety and stress and excitement. And a bit of panic. The irony is that we are not at all panicked about having another baby. Some of that may stem from our naivete about just how nutty life will be with a newborn and a toddler–or from the fact that we remember Finn’s early days really fondly, and we feel like we missed out on the often fraught exhaustion that sometimes clouds the newborn weeks.

But most of that is because we are both very worried about how Finn will fare during the transition. First and foremost, we’re stressed about having to leave Finn for the delivery. Of course, these things can’t really be planned, and the uncertainty of not knowing when Sona will go into labor–and who will be around to watch our toddler–is stressful. My mom is set to arrive on our due date, and she can hop a flight as soon as we call her, should Sona go into labor sooner, but she’s still at least a day away. To complicate matters further, my parents are going to be out of the country–on a remote, isolated Bahamian island–all of next week. So, there are 7 days in which they absolutely couldn’t be here.

Because of this, we have our favorite long-time babysitter on call. She’s got a bag packed and, should we need her to, she’ll be here to stay with Finn. But he’s never done an overnight with her–and he hasn’t done an overnight without us in well over a year. When you combine that with the fear and suddenness that will certainly accompany his finding out that we’ve had to leave without warning–and possibly without saying goodbye–and this momma is a nervous wreck about how all of it will go down.

So, for many reasons–those already mentioned, along with the fact that I have 10 days left in both the class I am taking and the class I am teaching–we’re really hoping that Elias hangs on until late July.

But regardless of timing–of whether papers have been written or graded or cribs have been assembled or grandparents are on standby–I have a seismic, raw ache and a pretty deafening sense of melancholy about letting go of the past 3 years in which Finn has been the most beautiful, spirited sun around which our little lives have happily rotated.

When we were pregnant with Finn, I experienced a similar ache, bemoaning the life Sona and I had lived as a twosome for 15 years. This is more acute, though. This is also accompanied by raging mom guilt–and by the knowledge that, whereas Sona and I can still escape for a week, pretending its just the two of us again–I know that, come early August, I’ll never again be able to have my whole heart so blissfully full of just one little boy.

Here’s the thing about being a mom: it’s a very different kind of love. It’s a love that warrants a special kind of attentiveness and care. A love that is engaged and active and alert. The way I love Finn won’t fundamentally change, I know, but the way I practice my love for him will have to, especially in the beginning.

And this is all, really, good. This is a change we prayed for and worked for and welcome. A month from now, I’ll be writing a blog post admonishing the fear and trepidation and sadness I am feeling now. I do know that.

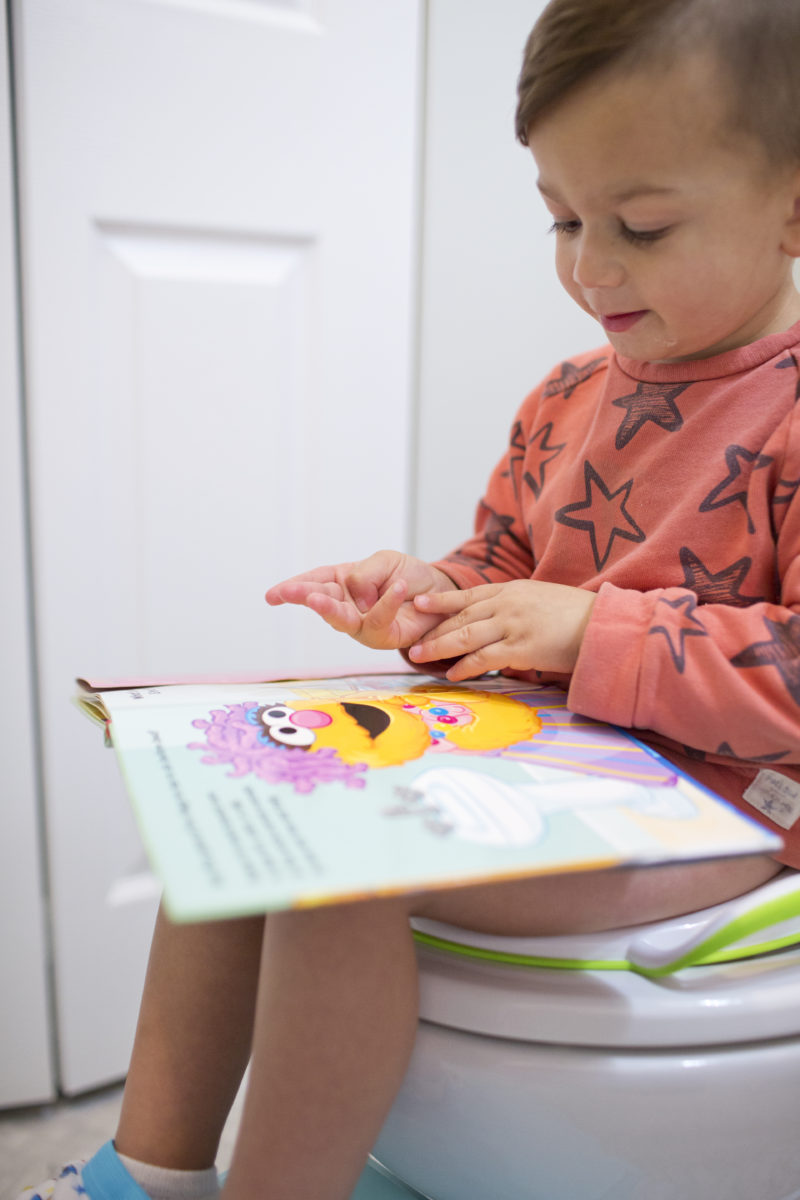

But right now, I just want to have a few more days with the little boy who is my sun and my moon and the thing I love most in the entire wide, scary, beautiful universe. We have 22 days left, hopefully, and I want to relish them as much as I can.

These photos are from a night a couple of weeks ago. It was on the cool side of warm, the sun was setting, and we decided to forgo bedtime and take an evening scooter ride to the beach. We walked the fog-draped pier, waved at kayakers as they headed towards downtown, and watched as Finn splashed around in the water, the city we love so much blurring into the background.

I stood on the beach that night and thought, “Damn, I’m so lucky.” And I am. I so, so am.