We’ve received a lot of supremely kind and generous feedback since we’ve started sharing our attempts to conceive baby number two. It means a lot that so many folks have expressed their well wishes, crossed their fingers, or–in many cases–shared their own stories, which are at once very different and eerily similar. Through these conversations, there are a few questions that keep coming up. So, I thought I’d take some time to answer them. Here it goes.

Is Sona pregnant, yet?

I get the impression that some folks assume this blog series is like a serial podcast–one with a predetermined end that has already been established but not yet revealed to the audience. I wish that were the case.

Hopefully, eventually, this will culminate in a pregnancy–and a healthy bambino. For now, though, I can tell you that, even though I’m going back to catch everyone up on the past several months, we are–as I said in my first post–still trying to conceive. If you follow us on Instagram, you know that we share a lot via InstaStory. You probably also know that we did an insemination 9 days ago. (We went InstaStory-crazy that night and shared a lot of info.) In hindsight, we think we likely got the timing wrong by a day, but we will test for pregnancy at 14 DPO (days past ovulation) and keep you posted on the results.

As of right this second, there is a tiny chance that Sona is pregnant, but we aren’t very hopeful.

How does all of this lesbian baby-making stuff work, anyway?

Okay, so few people have phrased the question quite that way, but the majority of responses and/or questions we’ve received have made it quite clear that folks don’t really understand how: 1. conception happens, generally and 2. the options available to lesbians TTC.

We have tackled both of those things via InstaStory, but I’ll review.

First, it is important to understand the difference between ICI and IUI. This has been a great source of confusion among folks, even other lesbians. (Hell, it was all a great source of confusion to us when we first started this process. That’s one of the reasons I wanted to write this blog. But more on that, later.)

So, ICI is intracervical insemination. It is the closest to sexual intercourse, as the sperm is placed into the vaginal canal, close to the cervix. The hope is, of course, that the strong swimmers make their way through the cervical opening and into the uterus.

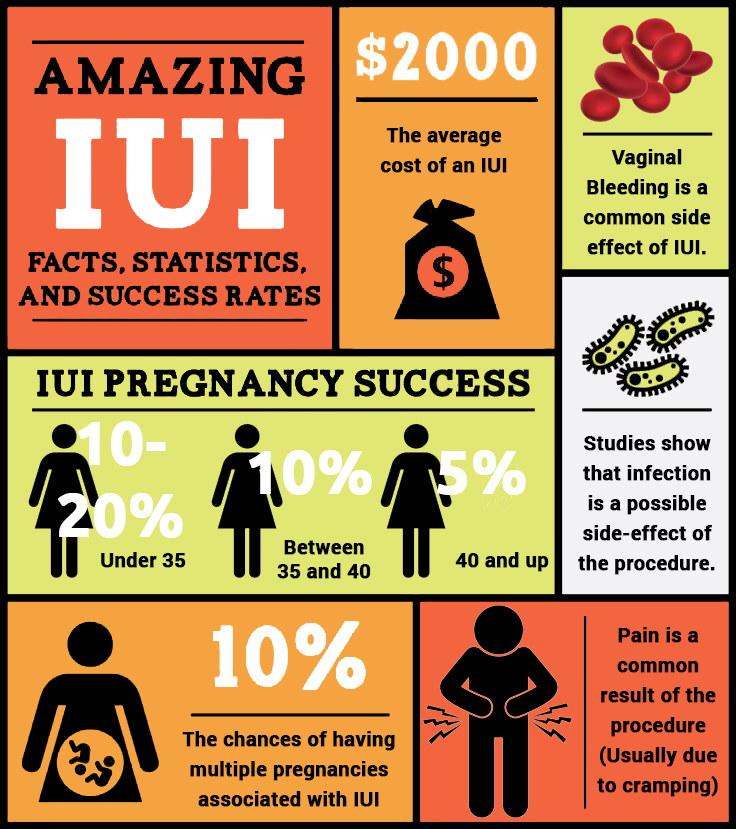

IUI, intrauterine insemination, actually places the sperm directly into the reproductive tract by going through the cervical opening and near the uterus. The chances of pregnancy are slightly higher with IUI, as you’re already getting the little swimmers through the first door, if you will. But this is also considered a medical procedure. It can be difficult to get through the cervical opening, and it could potentially introduce bacteria into the cervix. IUIs are typically performed in-office by medical professionals; ICIs are typically performed at home.

Also, the sperm you use must be specific to the procedure you are doing. IUI sperm is washed and free of all ejaculate fluid (I hope I never have to say that phrase again), as that can cause an infection inside of the cervix.

So, that’s your sperm education for the day.

Essentially, when lesbians decide that they want to have a biological child (i.e. not adopt), these are the options:

- Go with a known donor. Do an ICI with fresh sperm.

- Go with a known donor. Have sperm washed. Do an IUI with fresh sperm.

- Go with a sperm bank. Order either ICI or IUI-specific sperm. Do corresponding procedure.

- Do a procedure called reciprocal IVF. Harvest egg from mom #1. Fertilize egg. Implant in mom #2.

Because we didn’t want to know our donor and because we couldn’t afford reciprocal IVF (which I’m not actually sure we’d care to do, anyway), we chose option #3. Because there is a slightly higher chance of pregnancy with IUI, we decided to go that route.

Let’s look at a nice little infographic that gives some good stats about IUI, including the small chance of success each cycle and the high cost.

The low success rates per cycle (our docs said expect it to take at least 5-6 for a healthy and fertile woman) is almost entirely due to errors in timing. Timing is EVERYTHING with IUI, and it is what drives those of us who are TTC mad.

I’m not going to go too much into this, but here is my short–and rather unscientific–explanation. Frozen sperm is only viable for a maximum of 24 hours, but a lot of studies indicate that viability rapidly decreases after 12. A woman’s egg can only live 12-24 hours after ovulation, but the older you get, the shorter that window. There’s a good chance Sona’s egg needs to be fertilized within the first 12 hours.

Are you doing the math? That means that we have to have the 12-hour peak of sperm viability overlap with the 12-hour window in which Sona’s egg is happy and healthy. TWELVE HOURS.

This is why women take their daily temperatures and check the consistency of cervical fluid and pay attention to all signs of whether or not their bodies are ovulating. There are ovulation tests that predict when your LH surges, and that generally indicates that ovulation will occur with in 12-36 hours. However, do you see that even that window is too wide? Even within that, there is so much room for error.

To complicate things further, we believe that Sona is ovulating either BEFORE the tests indicate an LH surge (maybe her levels are low?) or very soon after. If she’s not testing 5 times a day, it is potentially very easy for us to miss when we window is. And we don’t think we’ve been able to nail it down, yet.

Fresh sperm can live for up to FIVE DAYS inside of a woman. (Start charging rent for that shit, ladies.) So, that’s why women are much, much more likely to get pregnant if they use a known donor and a fresh, never-frozen specimen. Their window is huge compared to those of us doing IUI with frozen sperm. 12 hours vs. 5 days.

Why are you sharing such personal information on this blog?

This is the one people have been afraid to ask, but I know a lot of folks are thinking it–even close family and friends. The varying levels of discomfort with our sharing our story are evident.

I started this blog, initially, for three reasons: First, I want Finn to have a recorded history of his life. I want him to know our journey, and I know that–at some point that’s closer than I’d like to admit–we will want to relive these memories, ourselves.

Second, I am a writer. I love stories. I believe in the power of stories. It is in my soul. I have been writing since I was a kid. I majored in English in college. I studied Poetry in graduate school. I am an English professor, now. Whether through fiction or poems or photographs or blog posts, I have always told stories. It is how I process the world. It is how I cope. It is the thing most dear to me in the world.

Lastly, as I’ve already alluded to several times, the stories I read on the internet–stories about families, blogs about motherhood, about trying to conceive–are almost always from the perspective of white, upper-class, mostly Mormon (right, tho?), hetero-normative couples. There are some stories that aren’t being told, and I want our own to help fill that void. I want to normalize our kind of family for everyone who doesn’t understand what it means to be a two-mom household, and I want to give other families like us the chance to see themselves represented. When we first started this process, I desperately sought that, and it was hard to find.

And now, I have a new, albeit lofty, goal: I want to demystify the conception process for same-sex, mainly lesbian, couples. I don’t want women to have to spend hours and hours doing online research, only to get half-true answers on discussion forums. Sona and I were so ignorant when this all started. We couldn’t find the answers we were looking for easily, but now we know a lot about the process. Often, we know more than the medical professionals who have helped us. That’s empowering, but it is also discouraging. We’ve learned to advocate for ourselves and for our family, and we want other same-sex couples to feel like they have the tools to do the same.

I love that you are providing such clear, helpful, and, yes, personal information. Too much necessary information is hidden because people think it’s too private. But where else will we learn if not from each other’s stories? Thank you for sharing.

Thank you for writting this. Both myself and wife have beeb TTC and have been facing SO many questions it is unbelieveable!

We live in the UK and there was little or no information when we started our journey and as you said it was only through internet research that we realised we could get help through our NHS. We are so luck that this is the case, but it needs to be more commonly known!